Spicing Up the Tropics, by Kristine Madera

First published in a food issue of WNC Woman Magazine

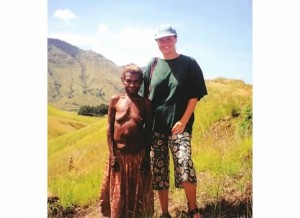

In the jungle of Papua New Guinea, there are few options but to eat the local fare. My husband and I were posted in the craggy rural mountains of this beautiful but primitive island country when serving with the Peace Corps over a decade ago. Just north of Australia, New Guinea is best known in the US as a battlefield between the Allies and the Japanese during World War 2, and for the fading practice of cannibalism. Among historians, New Guinea is also recognized as one of the earliest centers of agriculture, with evidence of irrigation going back 10,000 years.

Despite that early advancement, New Guinea never indigenously developed the wheel, architecture or city-states, probably in part because the country is over 75% dense rainforest, with remnants of towering, but deeply rutted volcanoes that make the terrain nearly impassable by anything but foot travel. The rugged terrain separated clan and tribal groups so effectively that there are over a thousand distinctive language and cultural groups in this country of less than seven million people. Most New Guineans continue to live in bush material houses, and many still wear very basic clothing made from pounded bark cloth. Like an island out of time, most New Guineans lived much the same fifty or a hundred years ago as they did 10,000 years ago. And current changes are slow to reach the more remote parts of this breathtaking country.

Despite that early advancement, New Guinea never indigenously developed the wheel, architecture or city-states, probably in part because the country is over 75% dense rainforest, with remnants of towering, but deeply rutted volcanoes that make the terrain nearly impassable by anything but foot travel. The rugged terrain separated clan and tribal groups so effectively that there are over a thousand distinctive language and cultural groups in this country of less than seven million people. Most New Guineans continue to live in bush material houses, and many still wear very basic clothing made from pounded bark cloth. Like an island out of time, most New Guineans lived much the same fifty or a hundred years ago as they did 10,000 years ago. And current changes are slow to reach the more remote parts of this breathtaking country.

In the absence of advancement in the Western sense of the word, the people of Papua New Guinea are sophisticated farmers and land developers. While village centers may lack paved roads, they grow boundary walls of hibiscus, poinsettia, and bougainvillea. In what may look like untouched rainforest can be a gently tended source of wild mushrooms, protein sources like edible insects, and marsupials like tree kangaroos, and even shade-grown coffee for export. Produce and pigs, the most prized of domestic animals, are the core of an elaborate system of traditional trading, a competitive system of ceremony feasting, and formed the basis for social standing. Gardens, especially in the varying climates and elevations of the highlands, generate a variety and abundance that I was told during our Peace Corps training would make eating local in our particular assignment area a gustatory pleasure.

So I was more than a little shaken when I went to the local market for the first time. On market days, dozens of women walked in from the outlying villages, arriving mid-morning after first plucking their offerings from their gardens and then trekking over miles of dirt roads and goat trails. Nearly always barefoot, they carried their bundles of produce—and often a baby—in hand-woven net bags that they draped down their backs from their foreheads. They congregated in a field near town and displayed their fruit and veggies for those of us with less time (or in my case, a complete lack of skill) to till our own fields. It was a great set-up, in theory, with all that fresh-picked organic food just a few coins away, and though I anticipated that there would be things that were unfamiliar, I expected to at least recognize something. Instead, I walked around in shock as I looked from one unidentifiable cluster to another until I went into overload and left the market in a daze—with no food. I wandered up to the district center where a local woman I knew found me. She laughed at my reaction to the market, but since she had traveled a bit, she understood the confusion of the unfamiliar and walked me back to the market to give me a primer on the local harvest.

Turns out that there were some things that I recognized, it was just hard to see them through the varied bundles of weed-looking bush greens, the piles of hard round sugarfruit that looked like yellow specked tennis balls, and the red egg-looking tree tomatoes (which I have seen since then—though a little squishy and droopy—in supermarkets here, labeled as tamarillos.) Dotted among the unfamiliar were half a dozen kinds of sweet potatoes—one of the staples of highland food, twenty kinds of green cooking-style bananas, and several varieties of pineapple, our favorite being a thin-skinned round variety that fit comfortably in my palm. We ended up eating one of those pineapples almost every night after dinner. I still count it as one of my favorite foods, even if it exists for me now only in my memory.

Each market visit I tried something new and discovered that some of those unrecognizable weeds were actually pretty good. One in particular, a velvety bush green so dark it was almost black, that sautéed for a minute or two turned softer than spinach and so rich with vitamins that it made me feel like Pop-eye after eating it. Another favorite were small, oddly shaped pumpkins so sweet that I would sometimes mash them into a sort of pudding with some cinnamon and powdered milk and just a drop of local honey.

For all that great produce, no one would ever use traditional New Guinea cooking and the word “cuisine” in the same sentence without a “not” between them. It’s not hard to believe when you consider that until fairly recently, most people cooked using hot rocks or open flames. Food like sweet potatoes were baked directly in embers and eaten dry, other kinds of food were cooked wrapped in banana leaves or stuffed into wide hollowed-out lengths of bamboo. Even a basic seasoning like salt wasn’t available in the mountains where we lived until roads and airstrips were built in the mid-20th century. There was a semi-salty, dirt-tasting “bush salt” substitute, but it really didn’t measure up, though it might have been salty enough to meet a body’s sodium needs.

For all that great produce, no one would ever use traditional New Guinea cooking and the word “cuisine” in the same sentence without a “not” between them. It’s not hard to believe when you consider that until fairly recently, most people cooked using hot rocks or open flames. Food like sweet potatoes were baked directly in embers and eaten dry, other kinds of food were cooked wrapped in banana leaves or stuffed into wide hollowed-out lengths of bamboo. Even a basic seasoning like salt wasn’t available in the mountains where we lived until roads and airstrips were built in the mid-20th century. There was a semi-salty, dirt-tasting “bush salt” substitute, but it really didn’t measure up, though it might have been salty enough to meet a body’s sodium needs.

Ginger grew locally, but it was considered a healing food for things like stomach upset, not a cooking spice. In fact, they considered any food with a strong taste, including onions, garlic, and lemons (all introduced, not indigenous), as medicinal. So, except for the powdered spices that we brought with us from the capital, the local food, as fabulously fresh and nutritious as it was, was sadly bland. We pleaded for some yummy zing from home to keep the old taste buds from dying of monotony, and my mom sent habanero seeds, which, if you’re unfamiliar, are some of the hottest peppers around. In the fertile volcanic soil, they grew like hedgerows, and people started to notice. Or maybe they noticed because it was us that grew it. For time, energy, and skill-set reasons, it was much easier to buy from the local market than to grow our own food, so I think that people were surprised that we could grow anything at all. Of course, we shared, and immediately the locals identified the strong-flavored peppers as healing and just laughed when we said we used them to zest up our food.

Way too hot for a flavor, they uniformly agreed, the habaneros achieved instant status as an experimental cure for colds, sore throats, respiratory ailments, and other things. They recognized the health effect of the peppers as readily as I experienced the super vitamin kick of my favorite Pop-eye bush greens. People tried stewing them in hot water with lemon, some adding ginger for a super-immune booster, and they could drink down those “medicines” without a flinch, and raving at the habanero’s detoxifying sweating effect, but as food it remained a no-go. It didn’t take long before the peppers began popping up in the local market, with people having dried the seeds and planted the peppers for themselves. The women at the market who sold them looked a little sheepish when I appeared, but business was business, and even this far from the city people did what it took to make a buck—or a kina in this case. I just grinned, glad that we could leave a little of ourselves behind in what was sure to become at least a local medical food.

The habaneros were almost commonplace by the time our two years in the bush were done, though no one had yet, despite our repeated suggestions, started flavoring their food with them. But the Anga, the tribal group that we lived among, are known for courage and ferocity, and I have to believe that at some point that will apply to the taste buds as well. I like to think that some hearty soul with an extended cold or the flu will develop a taste for their habanero medicine and start putting them in, say, soup. I envision that person secretly smiling at the yummy discovery, and slowly converting others. But even if that never happens, I’m thrilled that we could leave the people of our area a little healthier, if not a little sweatier, than they were when we arrived.

Let’s Get Social

About Kristine

Pushing the edges of my consciousness has been my passion for as long as I can remember. This has flowed me into writing, podcasting, and becoming a hypnotherapist to help others push past limiting perceptions and expand their awareness and possibilities, too. Welcome to my world. Thanks for visiting!