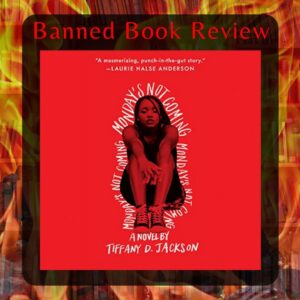

Monday’s Not Coming by Tiffany D. Jackson

Banned Book Review by Kristine Madera

Monday’s Not Coming is a YA novel that dives right into the murky question of what happens when a child, particularly a Black girl, disappears. When Claudia’s best friend Monday doesn’t show up on the first day of school, Monday is worried. When Monday doesn’t show up the next day, week, or month, Claudia becomes more frantic and insistent that something is wrong. The paths she goes down to find her best friend show the social and legal issues that limit what the adults around are willing and able to do to help. “You don’t get into other people’s family business,” is a common refrain, and the police detective that Claudia talks with shows her a wall full of pictures of missing girls of color, implying that Monday is one of a pattern of runaways or otherwise missing girls, and thus nothing uniquely alarming.

Monday’s Not Coming is a YA novel that dives right into the murky question of what happens when a child, particularly a Black girl, disappears. When Claudia’s best friend Monday doesn’t show up on the first day of school, Monday is worried. When Monday doesn’t show up the next day, week, or month, Claudia becomes more frantic and insistent that something is wrong. The paths she goes down to find her best friend show the social and legal issues that limit what the adults around are willing and able to do to help. “You don’t get into other people’s family business,” is a common refrain, and the police detective that Claudia talks with shows her a wall full of pictures of missing girls of color, implying that Monday is one of a pattern of runaways or otherwise missing girls, and thus nothing uniquely alarming.

Monday’s Not Coming is challenged/banned because of its depiction of violence, abuse, and neglect, and some adults fear that young adults should be sheltered from, you know, the reality of life for many people. To me, this fear is an extension of the general apathy toward the issue—if we can stop people from learning about it and caring about it, then we can continue to avoid doing anything about it. The issues brought up in the book are big and important and need to be addressed if we are to socially and even economically advance as a country.

Going into more of the story would be a spoiler, but in this video, author Tiffany D. Jackson says that the details of the story are based on two true stories, one in Washington, DC, where Monday’s Not Coming is located, and one in Detroit, MI. Much of the emotional journey of the main character, Claudia, mirrors the author’s emotional experience of having her best and only friend gone from school for a few weeks. She wanted to explore the side of missing children that are usually ignored—how do the friends, family, and communities of missing children cope and survive? Jackson also explores the importance of communities to their members and the deep cost when that community is lost, as with gentrification disrupting long-established neighborhoods. She also addresses the importance of getting mental health and other support when it is needed.

I’m more of a system thinker, and two big questions companioned me as I read Monday’s Not Coming.

First, in light of the rising parent’s rights movement and its “children are family business” mantra, how many rights do children have in the US? Turns out, not many. Though the UN adopted a Convention on the Rights of a Child in 1989, the US is one of the few countries not to affirm it—and not because it is committed to doing a better job. The US states all get a D or F grade when it comes to children’s rights, both in the stated rights of children and in recognizing and enforcing the rights children legally have. See more here. Most pertinent to this book, parents in all 50 states have the right to assault their children (within reason) and the ability to pull them out of school under the guise of homeschooling to hide outright abuse. Schools are the avenue most states use to track the welfare of their child residents. Most states have little to no way to monitor homeschooled children for abuse or even to be sure they are still alive. A child’s easiest way to report mistreatment or find support outside of their parents/family is often through school. But there are no reliable, legal avenues for a child to seek help and be sure to receive it. We treat children as the property of their parents to raise as they please. This is uneven at best, and tragic when a child’s parents or guardians lack the interest, capacity, resources, or intent to treat their children with care, compassion, and dignity. I’m no fan of government control over children, as that rarely works out well. But the system as it is, fails vulnerable children and needs repair.

The second question was, where are all the kids that went “missing” during the pandemic, and who is looking for them? Monday’s Not Coming was published in 2018, and the problem of missing children of all races has grown exponentially during and since the pandemic. Hundreds of thousands never returned to school after the pandemic shutdowns, and the increase in private school populations and homeschooling can only account for a fraction of them. Tens of thousands of unaccompanied migrant children and migrant children separated from their parents at the border are also unaccounted for and in significant danger of being exploited or trafficked as child laborers or sex workers. With all our talk about the value of children, we seem to value it more as a vote-getting mechanism because our laws and justice system are designed to fail children.

Books like Monday’s Not Coming, do us all a great service by helping adults, and young adults, see the world as it currently is so that we can make changes and create a better tomorrow.

Imagineering Protopia

As I imagine a better and more functional society, I always look at the core, organizing values and the incentives that shape laws and norms. Currently power, profit, and being on the winning side of the predator/prey dynamic runs the whole show in the United States, with ideals like the value of children, personal freedom, and environmental protection little more than feel-good talking points. To make true, lasting change in both policy and outcome, we need to connect our higher values to incentives, which are the rewards for corporate/systemic/personal/political behaviors.

Luckily, thoughtful people are looking at our incentives and how we might change them to create not only better outcomes and lives for children in each generation as we move forward, but better outcomes and lives for us all. In his book A Minor Revolution: How Prioritizing Kids Benefits Us All, author Adam Benforado J.D. explores the expansion and contraction of children’s rights and outcomes in the US since the child-protection movement at the beginning of the twentieth century, and how children went from being considered our collective responsibility to the responsibility solely of parents, whether they were adequate for the job or not.

Beforado argues that we need to put children first in all we do and rebuild our systems around children’s well-being, which he argues will elevate everyone’s well-being. For example, he suggests that we rebuild the criminal justice system around the needs of the children impacted. Punishing parents with incarceration severs them from their children, which deeply and irrevocably impacts their children’s futures. Tools like monitoring or intervention at the core cause of the crime, such as treating drug problems or addressing economic issues helps the parent, the children, the family, and the community and is much more likely to be successful.

If you don’t have time to read the whole book (full disclosure, it is still on my “to read” list) then you can get the gist of it in this print interview.

Re-imagining systems shift the focus from, say, re-structuring health care systems away from regulations that limit access and line corporate profits to making it accessible, affordable, and navigable for everyone. This improves not only individual health outcomes but creates a healthier society, boosts overall economic productivity, helps parents stay healthy so that they can take care of their kids, ensures that children are better able to stay healthy in the short term as well as build a foundation of health that will support them throughout their lives.

Harkening back to the issue of missing children, if we reshaped systems around the idea that children have an affirmative right to protection, food, shelter, education, caring caretakers, and community/government intervention when necessary AND a reliable, equitable, compassionate, and fair way to ensure these, many, many fewer children would fall through the cracks. The benefit would extend far beyond the individual child to all of society.

It’s not rocket science, but it does require imagination, compassion, political and community will, and a major shift in both the values we place at the core of our society and the incentives we use to prioritize them.

About Kristine

Kristine Madera is a #1 bestselling Amazon author, novelist, hypnotherapist, and pro-topian with a passion for helping people better themselves and the world. Informed by global travel, teaching abroad, and a stint as a Peace Corps Volunteer, Kristine believes that everyone plays a part in imagining and creating our collective future.

Volunteering at Mother Teresa’s Home for the Dying in Calcutta inspired her novel, God in Drag. She birthed her upcoming novel, The Snakeman’s Wife, as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Papua New Guinea.

Read the first chapter of God in Drag HERE